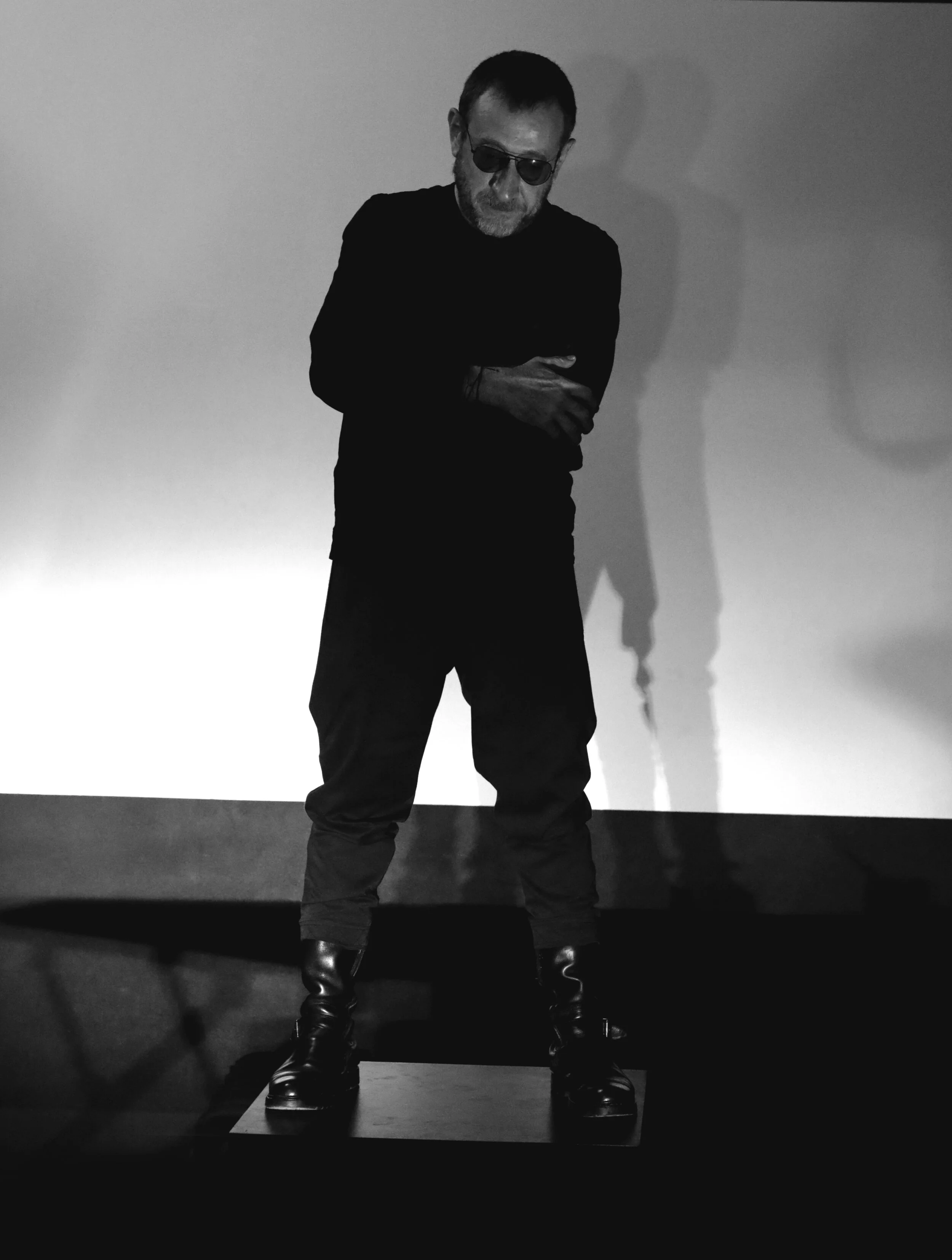

Bernard Khoury

Interview & Photography by Mart Engelen

Sometimes called architecture’s ‘enfant terrible’, provocative and controversial, Bernard

Khoury is known for his rebellious approach, categorical statements and unorthodox

buildings. Time to have a conversation with this world-renowned Lebanese architect

in his office in Beirut – the city he calls a “wonderful catastrophe”.

Bernard Khoury, Beirut 2019

Bernard Khoury leaving B018, Beirut 2019

Mart Engelen: You describe yourself as an architect of the present. But there is no present without a past and no future without the present. Can you explain to me what an architect of the present means to you?

Bernard Khoury: I am not one of those who feed on sugar-coated representation of my territories. I f nd that dangerously idiotic. I have given up on trying to formulate any sort of consensual history of the extremely complex and sometimes toxic realms I operate in. As far as the future is concerned, I would like to think that it would look bright, but I will not take off my shades… Our fathers and grandfathers were not so careful, which is why they ended up blind. The present can allow you to be more spontaneous. The present spares you the accountability that comes with the notion of history. Remember, I am an architect, I erect matter. I manipulate steel, concrete, and all sorts of heavy and permanent things. I am stuck in the Stone Age and I would rather not worry too much about the future. It will take care of itself.

ME: You also said the Lebanese are in denial after the civil war; there are very few cities in the world with a history like Beirut’s where present and past are necessarily so juxtaposed and so it’s hard for me to understand how they are in a state of amnesia as you suggested. Can you elaborate?

BK: Denial is a very typical condition in post-war situations. In the early 90s, many of us turned their backs to fundamental questions and the sour realities that were associated to our recent past; the f fteen years of conflicts, which in my opinion did not end in 1990. In fact, the war was not over. The war is still not over. It has taken different forms.

ME: We f rst visited your project B018, The Quarantine, a nightclub which you designed in 1998. Like a scene from a Mad Max movie, it consists of a circular black concrete slab, slightly elevated above ground level. You enter the club by descending a f ight of bare steps which lead you to a deep, dark, rectangular underground space. The nightclub was built in the industrial Karantina area of Beirut, close to the port where right-wing militias slaughtered Palestinian refugees camped in the area on 18 January 1976, at the beginning of the Lebanese civil war. How did you come up with the design and how did you deal with the history of the place?

BK: I often describe B018 as a place of nocturnal survival. Yes, the club was built on a site which has a complex history and a macabre aura. I’m often drawn to sites which are in convalescence. However, what touches me most is to hear the beat of that bass coming out of that hole at f ve in the morning, while everything around it seems to be inanimate. B018 is alive.

ME: I was also very impressed when I saw Plot # 1282. At f rst glance, when you are far away, it looks just like a warship but when you get closer the sharp lines fade away and you discover its very elegant forms. What more can you tell me about this?

BK: The story of our project on Plot 1282 is quite complicated. The urban fabric, on which it is erected, grew way too spontaneously with no regulating mechanisms. In the complete absence of the state, its institutions or any common projects. The plot’s 400-meter periphery intersectsts with just 6.5 meters of public domain at its tip, meaning that over 98% of its periphery faces private plots on which unpredictable private developments can be erected with blind walls that could go up to 50 meters. This means that our site could potentially be, in the near future, 98% a blind enclave with just 2% of its periphery subject to guaranteed setbacks. In such toxic conditions, I chose to embrace the totality of the site’s periphery with a continuous setback along 100% of the site’s perimeter, opening my arms and leaning back with totally naked clear facades, in a gesture of goodwill, awaiting our neighbours. I call this a suicidal masochistic act, but a very kind and generous one.

ME: Is there a reason why your designs have titles like B018, Plot # 1282, etc.? I am asking this because in your book Local Heroes you write that it would have been great if # Plot 450 had been called “The Man Overseas”. (laughs)

BK: Local Heroes is my take on very specif c events, and very exceptional individuals who made my projects possible. But Local Heroes is a book that belongs on the bookshelves of a very few, and that’s enough. Project titles have to deal with so many other parameters; that could explain why they hold such generic names, such as B018 or Plot 1282.

ME: This is my f rst visit to Beirut and I really sense an air of lawlessness. But also a freedom in the way people live. They seem to live from day to day. In the West, we are so restricted by government rules; in fact the free spirit of the Western world has been a bygone era for a long time. How do you respond, living and creating in this crazy city?

BK: No my friend. I am not crazy. Everything here is calculated very carefully. In fact, with the complete bankruptcy of the state, the incompetence of its institutions, the corruption of its political class, you are left with individuals with an incredibly high level of immunity. We are not the pampered citizens of the modern civilized world.

ME: I saw a def nite sparkle in your eyes at Plot # 450, the last project that we visited together and that will be ready by the end of this year. What an amazing building it will be. And there is also the amazing story of the client aka The Man Overseas who got you involved in this project. Please tell me more about it.

BK: Plot 450 and the project we are constructing on it are the result of an incredibly fruitful relationship I have had with The Man Overseas. The man who vanished right after the scheme had been secured and construction had taken off. The 150-meter-tall structure stands on a very strategic site, at the north-eastern entrance of Beirut’s Central District, also the former demarcation line between East and West Beirut. Facing it is the headquarters of the Phalanges party. To better understand our project, one has to know the history of this site and some of the key events it witnessed. I am thinking particularly of the f rst rounds of the 1975-76 conf icts. Our building not only addresses the site’s complex past, it also feeds on the phobia of security, which comes with dealing with a high-end residential fortress. And not a cute picture.

ME: How did growing up in war-torn Lebanon and being the son of one of Beirut’s prominent modern architects play a role in your decision to study architecture?

BK: I spent part of my childhood in Beirut, during the early months of the civil war. I also spent most of my childhood years living in buildings my father had built. I also sat, slept, and ate on furniture he designed … That did not traumatize me. The day I decided to study “Architecture”, I had to go do that very far from home, only to realize years later that the very pampered academic cocoons where I spent too much time did not teach me anything. Harvard is packed with sad, cynical, and wise idiots. From Khalil, I got the stubbornness, the sense of structural coherence and honesty, and of course a great dose of romanticism. And that is something the morons of my generation have lost. From Beirut, I got lethal muscles and the immunity to the bullshit that rocks the world of contemporary architecture.

ME: You are a creator of the present but how do you see the future of Beirut?

BK: I am having a hard enough time surviving the present. Remember, my practice (architecture) has imprisoned me in the Stone Age. I will pass on this one and will let the future take care of itself.

Copyright 2019 Mart Engelen

View of Karantina, Beirut 2019