Julian Schnabel

Interview & Photography by Mart Engelen

Julian Schnabel, Palazzo Chupi, New York 2018

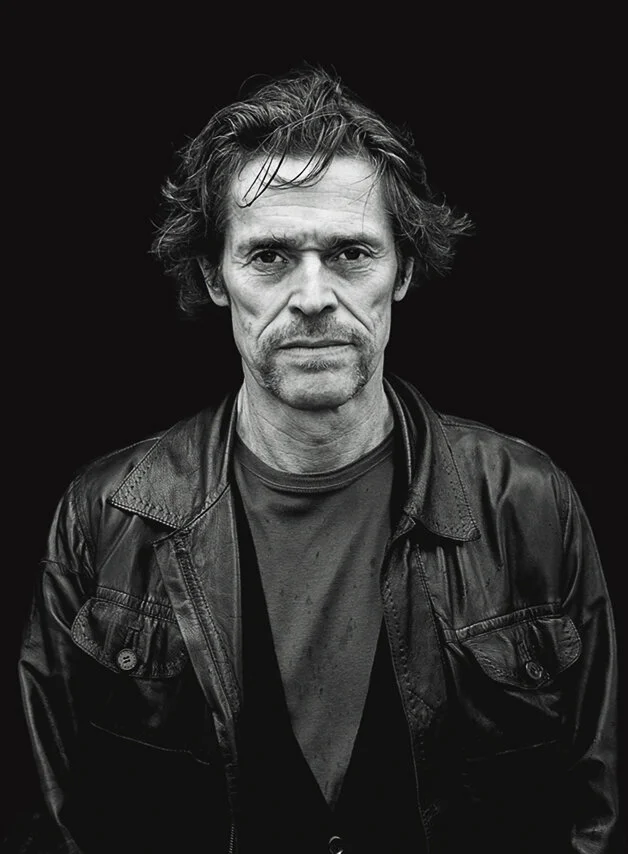

World-famous artist and film director, Julian Schnabel, talks about his latest film “At Eternity’s Gate” that centres on the final years of Vincent van Gogh, portrayed by Willem Dafoe, who won the Venice Film Festival’s Coppa Volpi for this role.

Mart Engelen: Everybody knows and has an opinion about Van Gogh. Did that put extra pressure on you to make the movie At Eternity’s Gate or, on the other hand, did it allow you to be more relaxed and free to make your own interpretation?

Julian Schnabel: That’s a good question. Hmm, we thought it would be impossible to make a movie about Van Gogh because everybody thinks they know everything about him. He’s the most documented artist who ever lived. So why do it? I guess after thinking about making the movie, and thinking about it for a while, you realise that maybe on the one hand I felt that everybody always gets it wrong. And it doesn’t make the chasm between the artist and society or between the artist and the audience any closer. In fact, it makes it more obscure. Then you realise the emotion of success for an artist is not about making money, it’s not about awards, all it has to do with really is the satisfaction or the sense of human gauge in the thing that you want to do and being involved in the practice of that. And inside that thing that relationship between the artist and what the artist wants to do is where everything happens. Whether you are a painter or a filmmaker. I don’t really know about filmmakers: I am talking about painting right now. Because now we’ve made the movie, people want me to talk about it and ask me to explain different things. People always ask me to explain art. Immediately you explain art, you’re lying. Art can’t be explained; that’s why people beat their heads about it all the time. They keep trying to do it. It’s very nice to explain things to make them seem more reasonable. But the opposite of truth is reason, not a lie. When you start to explain why, you are doing something else. There is nothing like the thing, there’s just the thing itself. One thing we show in the movie is Van Gogh is, like when people say ‘I read a beautiful article in the Washington Post yesterday’, absolutely brilliantly done. Very nice. But it’s because of its importance. The rest of what he had to say is very elusive. I didn’t see things in that theme before at all. In fact, I think from the theme ‘rich’: rich with the commitment and the conviction and the relationship that he had with the things he was doing. The idea about the incongruity of art and life. OK that’s a whole other issue. So I guess one thing that he does exemplify is the incongruity between life and art.

ME: When I saw the movie this morning, I perceived it as a beautiful serene composition: not like a movie. The blending for you as the artist, but also the author, to show the character of Van Gogh must have been quite challenging. And interesting to fill that in with Jean-Claude [Carrière] and Louise [Kugelberg].

JS: Well, I used my experience as a painter to share that with Willem [Dafoe]. How he holds a brush a certain way, how he deals with the materials in a certain way and even when painting a painting, one sees the drama. The audience can be a participant in watching that unravel.

ME: Yes, and you take your time for it.

JS: Exactly! It comes from his paintings. Not from the letters. People are looking from a distance. It’s extremely subjective and I took a lot of what I would call poetic licence. I mean, I know for a fact that Van Gogh never saw a Goya painting and he never saw a Velázquez painting because those paintings were not yet in the Louvre. But he did see Goya etchings. He wrote that they happened in his dreams but he never saw a painting by Goya and I thought it was more interesting or more compelling or provocative and also in concert to show a Goya and a Velázquez painting up close because you see the molecular nature of all of the strokes that comprise a head or a vase. If you look at a Van Gogh painting, you see the autonomy of all the marks. So that fractured space and that notion about understanding, getting the feel through marks, is something that I could show using those paintings rather than say a Millais or Gustave Doré painters that he may have liked. I wanted to honour him in that and so I took some liberties. The colour in Van Gogh’s paintings doesn’t come from reality, it comes from his palette. He also said, and this is something that Francis Bacon quoted in 1954 when making Van Gogh Going to Work, “How to achieve anomalies, inaccuracies and refashionings of reality so what comes out are lies, but lies that are more truth than literal fact.” And I would say that our movie is made up. But is it more true than literal fact? Maybe. We are leaning towards divine light to see if it will hit us. We also are going into nature, into the landscape where he was, into the locations where he was, letting the wind affect what we are doing and leaving it to Willem and all the other actors. Not telling them what to do. Setting up a situation where they can react with paintings and materials and architecture and the situation until what comes out are authentic impulses and keys that can illuminate impulses in Willem. One thing about painting is, I don’t know, you don’t have to know what it means, you just have to look at it and experience it. You don’t have to know if it’s good or bad. So the thing is that when you act and are free enough, you don’t have to make those judgements either. You just have to be who you are or who you aren’t at the same time.

ME: Well, it’s definitely beautifully set up and recognisable to see your influence in the movie maybe because it gives more reality than all the facts and figures that we’re not really interested in. I have to say it was amazing to see that you put the camera on Willem for such a long time and what he gets out of himself is really extraordinary.

JS: Exactly. And we are talking about what Van Gogh got out of himself and what he had to go through. And also what Mads Mikkelsen can pull out of himself. And that scene is eleven minutes. And most of it’s on Mads. An editor might want to say ‘Don’t you want to show the main character?’. Well, yes I do. But I want to show what the main character is experiencing so later when he says something, you know why he is saying it. There are densities and equivalences about what we want to show and how we want to tell the story.

ME: Some years ago, I visited many of Van Gogh’s places from Arles, Provence, to the Auberge Ravoux in Auvers-sur-Oise and finally where he was buried in Auvers-sur-Oise. I assume you also visited all those places. JS: Of course. But we weren’t able to shoot in the Auberge Ravoux because the owner was worried that the Van Gogh Museum did not replicate the drawings and also about the story about the boys. And if I kicked these things out, we were gonna shoot there. I said I couldn’t do that but he did tell me that when Van Gogh died they put his coffin on a table at the Ravoux and put the paintings around him. And I thought what a great thing to do. And he gave me that just by telling this story. And we ended up filming that scene elsewhere.

ME: A little bit later we have a great Spaniard called Picasso. Something I’ve always wanted to know that so far nobody has been able to tell me and that you don’t read a lot about, did Picasso ever make a statement about Van Gogh? Maybe you know.

JS: All you have to do is to go to the Musée d’Orsay. There was a Picasso Blue Period show at the same time as our show. I selected eleven of my paintings and ten from the collection by Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Monet, Manet, etc. But what I wanted to say is, when you see Picasso Blue Period works made in his twenties they were absolutely influenced by Van Gogh and not only that but also by Toulouse-Lautrec. You could see that in the Musée d’Orsay because all these paintings were in the same building.

ME: But he never made a statement?

JS: Well, I don’t know that. But he was very influenced by Van Gogh. ME: It’s always very important and difficult to choose the music for a film. Can you tell me more about this for this film?

JS: Yes, I think the music was difficult and important and very soulful and dissonant and it really felt like the nervousness inside him. Tatiana Lisovskaya created the music. Her first instrument is the violin but she plays the piano in the movie.

ME: Thank you for this conversation

JS: Thank you.

Copyright 2018 Mart Engelen

Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in “ At Eternity’s Gate”

Courtesy CBS Films

Julian Schnabel, Palazzo Chupi, New York 2014

Willem Dafoe, Amsterdam 2012