Not Vital

Interview & Photography by Mart Engelen

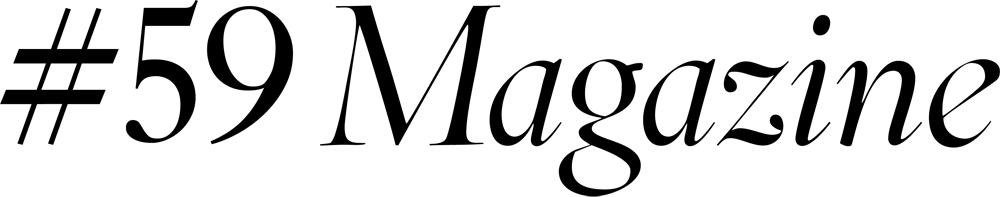

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac presented recently POLES, a new exhibition by Swiss artist Not Vital in the Paris Pantin space. Bringing together monumental sculptures, paintings, drawings and installations, this large-scale exhibition features a selection of Not Vital’s recent and new works from the last decade. Time to have a talk with this extraordinary artist about his art and nomadic life.

Not Vital, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris 2017

Mart Engelen: How did being raised in the Engadine, known for its wild and beautiful nature, influence you artistically?

Not Vital: Actually, in just about every way. First of all, growing up in the Engadine gave me the opportunity to form such a sane base. As a base, I think it was the best I could get. It interests me of course in many ways, for example when making a sculpture: the colour. There isn’t much colour in Switzerland and if there is colour, it’s white. My favourite material is plaster, which is not only white as snow but also has the consistency of snow. Another aspect is the way you look at things. You are Dutch, aren’t you? If I were Dutch, my sculptures would not be on poles but they would be at eye-level. In order for me to concentrate on something, it has to be exactly that high. I can concentrate much better looking up than at eye-level. So all these things have influenced me artistically but also in many other ways too.

ME: The title of this exhibition is Poles. You’ve been making them for many years but you made a whole new series for this exhibition. Can you tell me more about this?

NV: Well, I started making the poles in New York in the 1980s. I think I made the first one in 1979 or 1980. As I said before, raising up the sculpture was necessary for me to concentrate better on it. Of course, when I first showed this in America, people were really turned off by it. They saw something very cruel. Even today somebody said it’s really cruel, for instance, to put the Self-portrait as the Village Idiot, which I am, up there on a pole. I don’t see it that way of course.

ME: In what way are the poles of today, which look very polished and smooth, different from the first poles of the 1980s?

NV: They have changed a lot. In the beginning, the sculptures were made indoors, in the studio, but the poles today can also go outside because they are stainless steel. It’s not so much the shiny effect I am interested in but more that they can stay outside. In the beginning I used plaster, of course, and fur and asphalt. Maybe that gave the sculptures more of a sense of something that could have been done many, many years ago. I still believe, you know, that you can make something contemporary and go back let’s say 10,000 years. At the time, I kind of liked the idea that it could be something from another era.

ME: Can you tell me more about your specific interest in the interaction of art and architecture? And when did it start? NV: It started very early. I remember when I was three years old, in 1951, we had a lot of snow. There was so much snow that you couldn’t even see the house. We dug a tunnel and I would stay in that tunnel; I still remember how it smelled and the light coming

through it. It was kind of warm in there. I think that at that moment something clicked in my head so that I thought I should always try to build my own habitat. Then later on, because we only had to go to school for seven months, I built tree houses, etc. with my friends. When I went to Africa for the first time, I started to build houses like the House to Watch the Sunset (2016) or, for example, the one I built in the desert called House against Heat + Sandstorms that should be a house where I would be able to survive. There is an opening at the top so the heat can rise and it also prevents the sand entering the house. By the way, when we started to build the houses in Africa there was no measuring tape and after we had built three houses, they found out that they all had a height of 13 metres, so we said that it must be the right height (smiles).

ME: You have built these houses in remote locations all over the globe. When did you start to build them? I think everybody now considers these houses as art; do you consider them as art?

NV: No, I consider them much more as a habitat. Well, they’re not conventional houses. First of all, there is no infrastructure. They have no water, no light because the primary purpose in one is to watch the sunset and in another to avoid the heat, and so on. They’re all situated in the middle of nowhere. They have to be because then they become a myth. As a concept it’s already enough to create that myth. I call them ‘scarch’ because it’s sculpture architecture. ME: What artists influenced you when you were a young boy?

NV: We didn’t get many chances to look at art in the Engadine. But I was lucky to be exposed at a very young age to a great collection that belonged to a professor. There was Mondriaan, Miró, Picasso and many more. I was just twelve years old. I could take them off the wall and look at what was behind. ME: I don’t hear Giacometti…

NV: Giacometti was too close. I still don’t consider Giacometti …. How can I put it—it’s overdosed. We see it too much. And that’s exactly what he didn’t want.

ME: But maybe that’s because you are also from the Engadine.

NV: Yes, but there are always Giacometti shows. If you make something precious, you cannot keep throwing it in front of your eyes. We don’t see Brancusis all the time. We see a Brancusi show every three years maybe. I also consider Giacometti a great writer but I would have to agree with him when he said, “If I have a good friend, that friend would tell me to give up.” I almost understand that. For me, it’s the same thing. Of course, I had to have distance but, on the other hand, he is not there with the ones I really like. I really like Brancusi, he was much more radical. And later, there was an artist who I like very much called Matta-Clark, who was actually an architect, who did phenomenal interventions like the “splitting house”. But today there are architects who are more approachable like Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid. They are sculptors. You don’t need to put a sculpture in front of one of their buildings like they did in the sixties in New York because the sculpture is already there.

ME: You have such a nomadic life, travelling for so many years to places all over the globe. What is your view of the world right now?

NV: Right now, if you read the press we face a huge dilemma. But on the other hand, in general, as an overview, we have never lived better than now. Of course, many people are still suffering, but people have a better life. Actually my view, … I am not that pessimistic. We have to correct certain things, like for example the air in Beijing. But I have full confidence for the future.

ME: One day, when you are not here anymore, how would you like to be remembered?

NV: I want to be remembered very much like my work: nothing in one place, I don’t want to be in my grave, I’d like to be cremated, a little bit here, a little bit there. It’s already organised.

ME: Like you always travelled and still are…

NV: Indeed. In fact we are living on this planet, which is not that big, I am always curious, I have to see it….

Copyright 2017 Mart Engelen

Not Vital