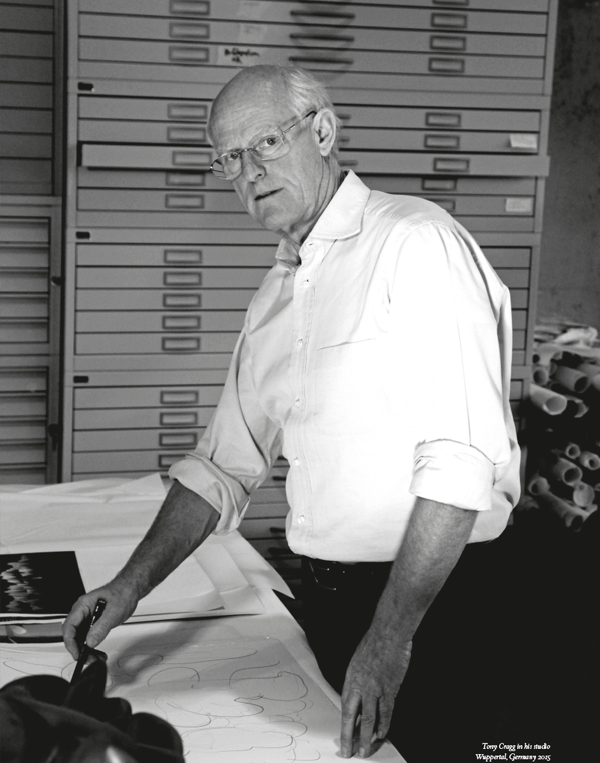

Tony Cragg

Interview and Photography by Mart Engelen

With important museum and gallery exhibitions coming up in 2016, it was time

to have a conversation with one of the world’s foremost sculptors about his life and art.

Tony Cragg in his studio Wuppertal, Germany 2015

Tony Cragg, To the Knee (2008)

Skulpturenpark Waldfrieden 2015

Mart Engelen: When you were a young artist, which artists did you admire? And who perhaps had an impact on your first work?

Tony Cragg: Well, I have to say, I did not study art in school; I didn’t have any art classes. My father was an engineer and we moved to many places where they were making aeroplanes. I went to seven schools, with different syllabuses everywhere. And I was actually more interested in science. I just started to draw because it fascinated me and it was exciting to do. I wasn’t thinking about other artists and I didn’t know much about other artists. Then I went to art school, which I was very nervous about:

I would be with very highly creative people: a new world for me. It was a very traditional academic school in the west of England, in Cheltenham. You were taught ceramics, life drawing, still-life drawing and one day half way through the course they said, “Next week you are making a sculpture”. I thought “Oh”. This didn’t sound exactly what I wanted to do. I was quite resistant to the idea of doing this but when I started, it was fascinating because everything you actually do with the material makes you have a different idea about it. You have a different idea, a different association and a different emotional level with it. It’s really interesting. It’s just like drawing. Because of everything you did with it, you changed the material and it changed you. And that was very powerful. I did it for

a week and after that I went back to drawing and painting. After that course, I went on a painting course at the Wimbledon School of Art on the outskirts of London. It was a completely different time. And all the time I had a real deficit in art history. I really didn’t know … I mean, you know, there was pop art. In Britain, David Hockney was a famous artist.

ME: We are talking about?

TC: 1970. In 1969 I went to art school. I started the painting course and I felt I did not want to paint. I knew it was too cramped standing in front of an easel and all that. Then I started to make things by tying knots in pieces of string and doing. Just by using material, I got into something. It was an amazing time because I found out, and obviously everybody knew about, Henry Moore and the Armitage and Chadwick generation. Even more exciting, I was twenty years old and you were hearing about Gilbert & George, Barry Flanagan and all these people. The American artists, Minimalism, Arte Povera. An enormous world. So there was not, like, one figure. Suddenly I realised there was so much depth of emotion involved in the debates around these things. You could see them as conflicts, if you like. They were ideological at times but they were aesthetic conflicts. Now I look back at this time and I think “What a privilege”. In Britain at that time there were so may facets going on in the country itself and the art schools were very much part of that. So it was just a great time to get involved in sculpture and that is where I came from. So it was not a fascination with a particular artist. Now I have my favourites and things that don’t interest me.

ME: So that was in 1970, and in 1978 you moved to Germany. Was that because of what you have just said about the enormous influence of all these facets at the time?

TC: Absolutely not. I was very lucky. I studied in Wimbledon for three years, finished there and was given a place at the Royal College of Art. It was a very luxurious situation and I was able to study for six years. In that time, I created my first exhibitions in the mid-seventies, one-man shows, and was involved in group exhibitions. The new things of the time, Conceptualism, Minimalism, etc., that really impressed me but I realised that wasn’t my generation. I realised I didn’t want to do that. By the early seventies there was punk in the air. Britain was not a happy place. It was socially very unequal. A quite violent society. This was before Thatcher, and Thatcher arriving didn’t make things much better. There was a lot of tension in the air. And we were sick of the status quo. And then I met my wife, my first wife, who was from Wuppertal. In 1975, I was in France, in Metz, for a year. Wuppertal was nearer to Metz than London, it seemed to me. So I was more in Germany and I thought I might as well learn German. When my studies ended in 1977, I came here because my first wife was born in Wuppertal.

ME: Does the current situation in the world have an influence on your work?

TC: Absolutely! I mean even at the beginning of the seventies, the biggest subject around. I mean sculpture has made a fantastic development over the past hundred years. At the end of the nineteenth century in Europe, all sculpture was figurative and used very few materials. Sculpture has become a study of the material world. So this is a fantastic new development. Maybe I couldn’t put it that way in the early seventies but I mean that is what one felt: it could be anything. What I do feel though, sculpture is a radical activity—a radical, rare and human activity. We know what everybody else is doing. We know how many cars, tables and pizzas are being made. But how many kilograms of sculpture are being made today? It is a very rare human activity. In the early seventies, the discussion was between form and content. And nothing has changed. It’s still about form and content. But there isn’t the conflict.

ME: So there is no conflict?

TC: It is not a contradiction. It is not an exclusive problem. That doesn’t mean there is only form or there is only content. They’re not mutually exclusive. They cannot be mutually exclusive. For any form there is always content. And any content must have form. There was an enormous row going on in the seventies about this. I didn’t belong in this critical situation when I was a student. I grew into it. Nowadays we live in a world … I mean, what kind of content is there? We live in a world where human beings are using materials all the time because we use them as an extension of our own selves. With our clothes, chairs, tables, rooms and so on. So this is an enormous material extension. All of that is utilitarian. And utilitarianism is always subject to lowest common denominated decisions. And that is why it doesn’t matter what city you are in, there is the same window, the same window frame, lamp. The same everything. Flat surfaces, right-angle corners: everything is boring and repetitive. Because human beings make dumb decisions. Utilitarianism forces us to make dumb decisions about the forms we make. They are always simplistic. Industrial systems run on the lowest, most economical form of geometry. Round, flat, straight. Sculpture is not bound by utilitarianism and therefore it grows into

space. In ways it’s free, it can go anywhere. With that freedom you are allowed to experience things. You don’t experience things walking through the city, through this already-repetitive architecture. If you accept this argument (which is true), everything you have in your head has come from the material world. You are born with an empty head. The information comes into your eyes, ears, mouth, skin. The material world has made us physically. It has taught us to think. And it has given us languages. So every term we have has been found in the material world. Why would a sculptor be a materialist? Of course, we are. The word materialism became a cheap word. But everything we know is material. Normally we use science to look at materials but that is a too limited way. You need art—you know, science discovers the material world and art investigates the material world in totally different ways. Coming back to the debate of content and form, nowadays content has become a kind of prerequisite ingredient of an artwork. But making sculpture is a radical, political statement.

ME: How do we see the current situation visually in your new work?

TC: In my early work I was interested generically in material I could get my hands on. You can say from a student’s point of view, I had no money, I had to find whatever I could. Doing that led to all sorts of things. For example to what extent a human being is not part of nature anymore. When I had the opportunity to exhibit in the late seventies I did a lot of work using things like plastic fragments, found objects or whatever. That was a very important time for me. But too often I stood with something in my hands thinking that if I had more time to work with it I could probably make something interesting out of it. In the early eighties, I realised I had to go back to my studio, had to change that way of working. I took certain things out of all the early work I made and I

still have a big store of objects I collected and everything. For example the colours of what they use in industry. Boring! Nothing like nature: beautiful colours—and then look at what happens when human beings make them. And then the simple geometries in utilitarian things. You take a big pile of plastics and you look at it. It’s flat, rectangular. So I started to work and thought what happens if you take these geometries and make them work in such a way that they start to have an emotional quality. An example of that would be a work I made called Minsters. Piles of round objects on top of each other. They were not fixed so they grew up in long, pointed things and they were obviously very geometric because of the circular format. But they had other qualities. I was forced to fix them because people would try to shake them to find out if they were loose. The next step…

ME: When was that?

TC: Well, I made the first Minsters in the late eighties. And I made the first elliptical columns in the mid-nineties.

ME: When did you make your first Rational Being?

TC: The very first one I called Rational Being was a carbon-fibre work that has been in the Castello di Rivoli in Turin. I think that was in 1996. Actually there are two big groups: one is Rational Beings and the second one is the Early Forms.

ME: I am very impressed by the Rational Beings. Can you tell me something more about them?

TC: The principle of Rational Beings is a very relevant one. The human figure looks very organic. Without the geometry of the molecules, our cells, bones and muscles, we would be a messy fluid on the floor. Terms like organic or geometric are … they are not necessarily opposite, they are facets of the same thing. In the world generally, we can say that geometry is a kind of intellectual, rational part and on the other hand that organic is perhaps more visceral. And already something that has been going on in our history for hundreds of years is starting to emerge: emotionality is being taken over by rationality. And emotionality has taken over rationality. It’s a kind of development of our civilisation. But it’s inherent in all of us. Because we continually like to make sure that we are making the right decisions. But 95% of everything we do is driven by emotional decisions. Not by thinking about them. And even when you go back to the sculpture of the nineteenth century and you have these muscular figures, I believe when we look at the material world, what we really want is psychological pressure to look underneath the surface. Seeing our faces is very interesting. What is this man thinking about? We cover our bodies but it’s quite interesting to know what is under everybody’s clothes. Looking at the sculpture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was also about energy; the outer surface is only a result of the things going on inside. Some of them are energetic, some of them are psychological, metabolic, and others are just geometric. There is always a reason for the surface. This is a difficult thing for me to describe. If you start to use material, a piece of clay or a pencil on a

paper, you have infinite possibilities. Every time you touch the material, there are infinite possibilities in it. The artist tries to sort out where there is meaning because not everything has meaning. So we are working with the material, and what is left—the result—has been kind of edited out of all the possibilities by the artist. And that is very much the case with sculpture. It’s not about what you can do, because I can make anything. The question is what did I end up making. We live grace of the high-level decision-making of an artist; this is what we get from the artwork. And I actually think that is the beauty of art. I mean I don’t want to rationalise it, it is still an emotional thing.

ME: When you start a new work, at what point does it become a work of art?

TC: Oh. [silence] That is a mean question! I don’t think anybody knows. An artist, in the ordinary practice of an artist, knows he’s making artworks. He knows he’s making a work. He’s just kind of deciding momentarily where he can stop. I think the material is quite decisive in it. Because if you keep changing the material at a certain point it just becomes exhausted. There is no point in going on anymore. I tone the question down a bit. I am currently working in the studio on something like thirty-five works. Some of them I have been making for two-and-ahalf years, and others I maybe thought up at the end of last week. Very few of those things I have started will become works I am happy with.

ME: Should art be provocative?

TC: Hmm. [silence]. What’s the difference between provocative and stimulating? I think that art just to be provocative is not interesting. We know that’s easy. But I think making art is always … it’s material on the periphery, it’s at the edge of what humans have made with material. And therefore it’s always a new frontier. And therefore it’s always thoughtprovoking. When people say provocative nowadays, you expect a negative reaction. Thought-provoking, emotion-provoking, I think it does have that but I don’t think that’s an aim in a work. I think it’s the wrong way to think about it because we can always provoke.

ME: Can you explain to me, for example, the emotion you experience when you see your work Points of View in your Skulpturenpark Waldfrieden?

TC: I get emotional when things change a lot. For me, emotion has very much to do with the rate of change of things. A very still emotion from just looking out across the ocean can be very tranquil. But the minute things sort of move around me very fast, for example a train rushing by, or people: I find this a more emotional content. In Points of View there are a lot of transitions from figurative to abstract and, as you move around, the face grins at you, it grimaces at you, it disappears. The more I walk around the work, the figure is sometimes threatening, funny or ridiculous. I can’t dictate what emotionality is, I can only say for myself. But it can become unpleasant as well. If the changes are so hard, it can also become a kind of conflict of form. Sometimes this confusion or conflict of forms is a metaphor for the conflict going on in my own head. Where should I go for dinner this evening? Or what work should I make less? Religion and so on. We live in a world today where a lot of our life is based on science but we all have to rely on our beliefs. We base our lives on our beliefs and a little bit on science. That is a conflict.

Copyright 2016 Mart Engelen

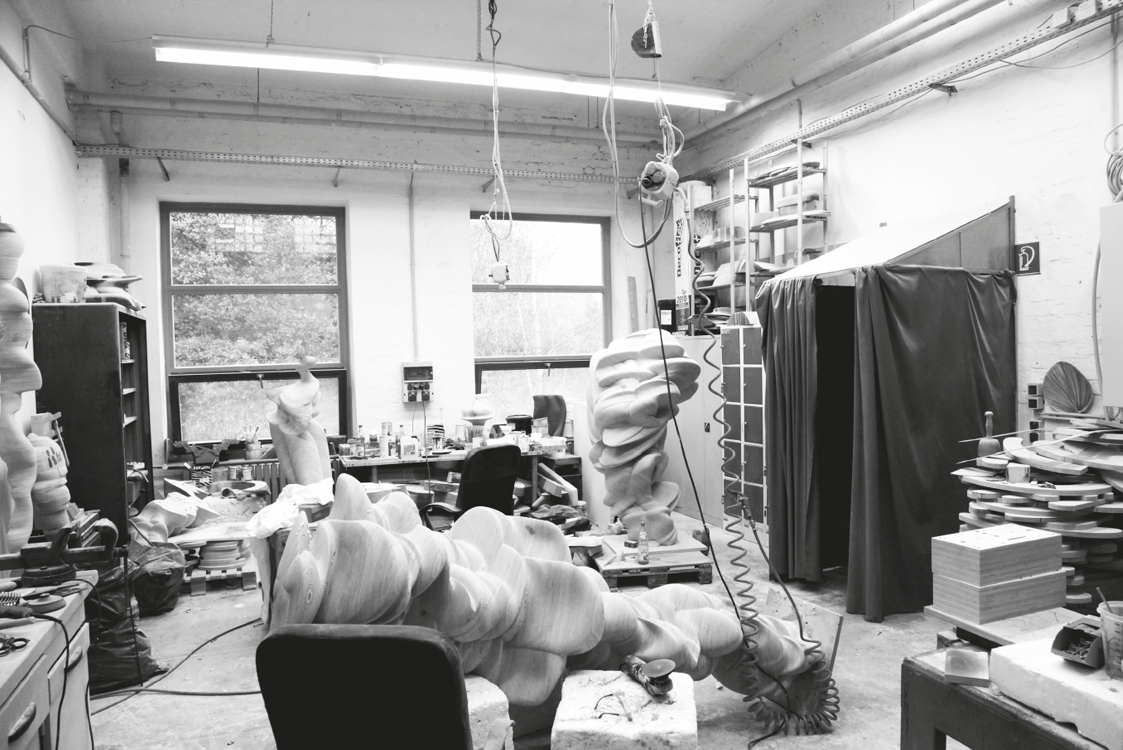

Studio Tony Cragg, Wuppertal 2015